(This is the second part in a little series of thoughts on confession. Here’s part one.)

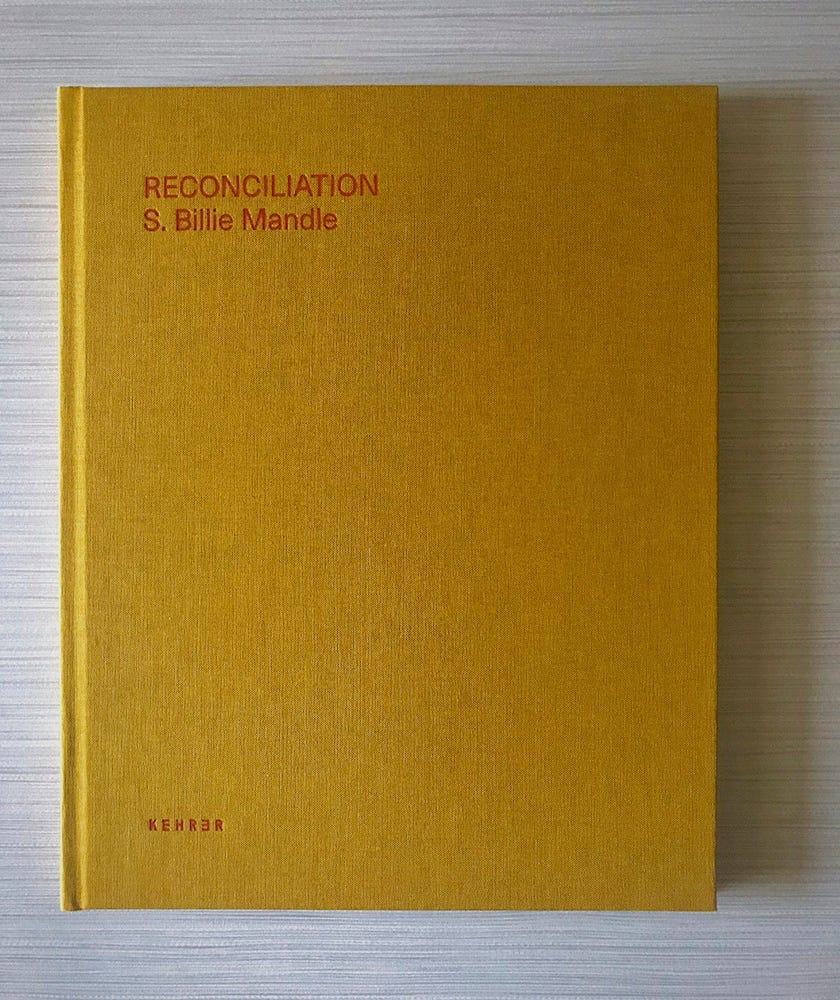

Reconciliation, Billie Mandle. Kehrer Verlag 2020.

In 2007, S. Billie Mandle began a ten-year project photographing confessionals in Catholic churches across the United States.

An artist and professor at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, Mandle is also a queer woman who grew up in the Catholic church — a church that is not affirming of her sexual identity — a church whose recent history of sexual abuse and coverup came to light around the same time she began her project.

So I guess I expected her photographs to be (rightly) angry. For them to be protest art.

But that’s not how they feel. They feel suffused with light.

In the earliest days of photography, “the attempt to record and fix a permanent image was seen as almost magical in its effect and suggestiveness: an alchemical process of transformation akin to revelation,” Graham Clarke writes; “a literal record is transformed into a metaphysical moment of fixed transcendence.”1 In the iPhone era, we’ve lost this magical association with photos, but Mandle’s images revive it. They transform and reveal: they take a period of time in an empty, sacred space, and allow the light to work — to write, as in the literal meaning of the word photo-graph(light-write), its own meaning in the space.

The act of photographing the confessional becomes its own sacred ritual for Mandle. Using a large format camera, she photographs with available light. She sets up the camera and walks away, sometimes for half an hour, for the exposure. The images, then, are lit “over duration,” and the way time and light unfold transform the spaces. Finished prints revealed things she couldn’t see when setting up the camera: light in the shape of a cross, water stains, dirt and grime, rich color. For her, the long-exposure images did what sacraments do: they made grace tangible.2

Billie Mandle found her ability to see transformed through the course of making Reconciliation. “At the beginning,” she says, “the images were a little bit more literal, and I was a little bit more tentative...I felt a little more reverence and desire to represent them accurately. And as the project went on, I felt more license to abstract the spaces, to play with the light. I grew increasingly confident in my ability to play with the light ...when I first began the project I didn’t know what that light would look like as it was transformed over the long exposures, and towards the end, I could see a dark space and I knew exactly what the light was going to look like after a twenty minute exposure.”

The longer one spends with the light, the more one is able to see the reality that light exposes in all things; this is true for the photographer and artist, and it is true for the Christian, too.

It is part of why we go to confession.

As the Christian sits in the place of confession, admitting need, exposing himself to the Light of God, he doesn't just experience forgiveness — he is able to see himself anew. As he sits with his sin and with Jesus, the light exposes the damage of sin, the water stains and the torn linoleum and the worn fabric and the peeling plaster, as occasions for beauty. It reveals the grain of the wood, the warmth of the colors, the shadow in the shape of a cross. To expose our faults and sins to the light is to allow Christ to make them beautiful: to see them as a happy fault, a disaster that brought redemption, that brought a more perfect perfection than that which existed before the fall.3

The space that seemed empty becomes indeed empty of sin, for those sins are (as Julian of Norwich saw and said) no-thing, are nothing that can separate you from the love of God; and instead of emptiness, this place is filled with light, with the presence of the one who fills the empty spaces in you and makes you whole, the one whose love is making all things well.

In Mandle’s images, no residue of the confessed sins remains. Only the light, and an invitation to play with the light, to learn from long experience with it how it transforms a place. How it transforms you.

Three Things:

“Look at What the Light Did Now,” one of the songs in my head when I write about this

Listen to S. Billie Mandle discuss this project with Kirstin Valdez Quade, hosted by Image.

This Chocolate Stout Cake with Coffee Glaze is tender and moist and not too sweet. Maybe a recipe to bookmark for St. Patrick’s Day. I used an organic chocolate stout, and Hershey’s unsweetened cocoa powder for all the cocoa rather than using two kinds. I didn’t have any whiskey, so left that out, and I used chocolate sprinkles instead of cacao nibs. Cake for breakfast!

The new album from Madi Diaz is on repeat for me this week; try “God Person.” (Something about her voice and the arrangements reminds me of Sara Groves albums I used to listen to twenty years ago.)

Dangerous Territory is now available in an updated second edition and as an audiobook! Buy it in paperback or ebook at Bookshop, Amazon, or Barnes and Noble.

Where Goodness Still Grows is available wherever books are sold.

In his book The Photograph.

So she says in that Image interview.

This is a little doctrine called Felix culpa, and here is it’s wikipedia entry

I like the light imagery / analogies--but reject "fortunate fall" theory: I'm for in spite of--not because of. Or even Kintsugi: broken and repaired, with brokenness acknowledged, and used not glorified. But yes, thanks for letting the light penetrate my confession: I need that part.