what happens to horse girls who grow up

they write two thousand words analyzing a children’s book

I was a horse girl. I can’t say exactly how long the phase was; there were three summers at a camp with horses (and creeks, and bows and arrows, and a rappelling tower); there was at least one wall calendar, and pages and pages of my own drawings; there was Billy and Blaze, and Black Beauty, and The Black Stallion (and the whole series that followed), and maybe most of all there was Misty of Chincoteague. This weekend, in the frustrated realization that ever novel I’ve read in the last four months has been mid at best, I pulled Misty off my shelf, desperate enough to risk returning to a childhood favorite — will adult me see racism or misogyny or shoddy writing? What if a re-read mars the beauty of the book in my memory?

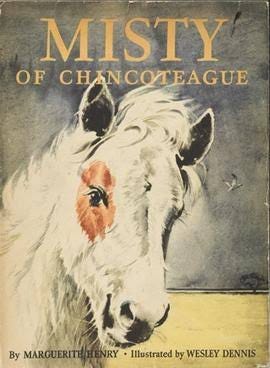

The story of a brother and sister who live with their grandparents on the island of Chincoteague and who want a horse of their own, Misty was written by Marguerite Henry and published in 1947. It was her 12th of 59 books, and not the one she won the Newberry for, but probably the one that has endured longest in the public imagination.

Every year, Maureen and Paul help their grandparents with ponies, and every year, the ponies are sold and they have to say goodbye. They want a pony they can keep, and so they devise a plan: this year, Paul is old enough (and man enough — girls and women don’t participate) to be part of the pony penning day, traveling to the island of Assateague and capturing wild ponies, descendants of Spanish horses from a shipwrecked galleon centuries ago, and then swimming them across the channel to be sold in a fundraiser for the fire department. (It’s a real annual event.)

For months, the siblings rake clams and gather oysters and catch soft shell crabs and clean out chicken houses and “gentle” their grandfather’s colts so that he can sell them at a higher price, saving $102 so that they can buy a pony. Of course they don’t want just any horse: they want the Phantom, a mare no one has been to capture. When Paul encounters her, he finds that she’s not alone. She has a foal; Paul names her Misty without even thinking about it. Through a series of adventures and setbacks, the siblings buy the mother and child, train them, and a year later, the Phantom even wins the annual horse race. But the day after, they’re out riding, and her stallion from Assateague swims across and calls her to return to the island. The children know this is right, and let her return to her free and wild life across the channel.

It’s not a particularly unique story — I imagine it pitched as The Boxcar Children (1924) meets The Black Stallion (1941) (though in reality, it was an idea pitched by an editor to Henry, who was a midwesterner — she traveled to Chincoteague to do her research and found a real-life story that inspired her) — it checks the boxes you expect, orphans, obstacles, independence and ingenuity, triumph.

These are probably the reasons I loved it, as a child — not just the horses, but the children who got to act like adults, who got to own a horse.

Re-reading it this month, though, I wonder if half of what entranced me was something I wasn’t able to name then, only intuit: the story told by the metaphors.

Before I get to the metaphors, though, as an adult I’m wrangling with the plot, which turns entirely on money: the children gather creatures from the sea and sell them to earn money to buy a creature from the island. Disney’s Pocahontas starts singing to me. Do I think we own whatever land we land on? Do I think creatures exist to be bought and sold at human whim?

Capitalism is the water the story swims in, I guess. But hints throughout the story salt its view of ownership with interdependence, suggesting that care matters more than capitalism. Pony penning began not as a moneymaker, but as a way to curb overpopulation on a small spit of land. The money earned from the sale of horses at the penning goes to the fire department, not to individuals, because on this storm-prone, isolated isle, they won’t survive without it. The children don’t earn money so that they can make more money; they earn money so that they can have a lasting relationship with another creature, rather than one that has to end. Then, of course, there’s the ending, the Phantom — purchased for a hundred dollars — returning freely to her own island a year later. The kids bought the Phantom according to the rules of the system they were born into, and then, with their grandfather’s blessing, they reject the system.

Human beings, in the ethics of this universe, exist to care. They give days to cleaning chicken stalls and horse stalls. They watch out for resource depletion. They eat the food they catch. They let animals live in the way that is best for the animals.

The relationship between a human and a horse, or a human and the sea, isn’t one of ownership; it’s one of care.

You can see it in the plot.

But you can see it just as clearly in the language. From the very first pages, metaphors don’t simply anthropomorphize animals. The language continually blurs the lines between animals, humans, sea, and land. Animals are like humans, humans are like animals, animals are like the sea, the sea is like an animal, the land is like the sea.

In the first chapter, which goes back in time to the shipwrecked Spanish galleon, the captain of the ship can only think of the ponies as commodities, even as the storm winds kick up.

“Gold!” He mumbled. “Think of trading twenty ponies for their weight in gold!”

The sea, as if in response, becomes “a wildcat… and the galleon her prey. She stalked the ship and drove her off her course…She cracked the ship’s ribs as if they were brittle bones.” Once the ponies have been freed, the sea becomes a kitten.

If the sea is like an animal, the new land the horses find is like the water, its grass billowing and shimmering “like the sea.”

The ponies’ journey is given biblical weight — they forget “the forty days and forty nights in the dark hold of the Spanish galleon.” Having survived catastrophe born of sin and evil, they can start afresh, like Noah in a new world. And in this new world, all creation has agency, emotion, purpose. “Spring tides had come once more to Assateague Island. They were washing and salting the earth, cooking new green spears to replace the old dried grasses.”

When a boy and girl appear upon the scene, centuries later, “The heavy beach sand seemed to pull them back, as if it felt that human beings had no right to be there.” Even so, they almost disappear into the picture, as if they are part of the whole of creation: “In the early morning light the two figures were scarcely visible. Their faded play clothes were the color of sand, and their hair was bleached pale by the sun. The boy’s hair had a way of falling down over his brow like the forelock of a stallion. The girl’s streamed out behind her, a creamy golden mane with the wind blowing through it.”

Paul recognizes they don’t own the place, though. “If you look close,” he whispered, “you can see that the wild critters have ‘No Trespassing’ signs tacked up on every pine tree.”

The animals are regularly described as humans: the sea birds are “like scouts” in wartime, the stallion herds “his family like a nervous parent on a picnic,” the horses lower their heads “like children being punished at school,” and Misty preparing for her race reminds grandpa “of a girl gettin’ beautified for her first dance!”

But the horses are also compared to other animals and other elements. The Phantom, grandpa says, “ain’t a hoss. She ain’t even a lady. She’s just a piece of wind and sky.” Phantom is “like the topsail on a ship — a moon-raker she is!” The horses are like oysters, and puppies, and seabirds, and cornstalk, and Misty racing is “a piece of thistledown borne by the wind, moving through space in wild abandon.”

Anthropomorphism is common in writing about animals. But what struck me about this story was the way that humans were also compared to animals and plants. Grandpa in the distance has “his gnarled arms upraised like a wind-twisted tree… Then he took off his boots and socks and dug his toes in the and, like a fiddler crab scuttling for home.” Grandma’s face is “round as a holly berry, and soft little whiskers grew about her mouth, like the feelers of a very young colt.” Paul laughs “like a spirited horse” and Maureen is “like a fly in a web,” trapped in the crowds at the horse race.

Everything is something else. Facts are “like water bugs skittering atop the water” and the air quivers “like a violin string.” Bones are sacred, even ship’s bones.

Each child experiences a moment of mystical communion with their horses. When Paul is searching for them during an intense storm, he realizes that they and he “are fellow creatures caught in a storm, prisoners of the elements. Prisoners together. Together! The word sounded a bugle in Paul. Time stood still. There was only the wind and the rain and the three creatures together! Together!”

When Maureen is watching the horse race, she thinks that “only by being alone could she be Paul and Phantom both” during the race, and in her meditative focus, she does become one with them.

*

Animals are like humans, humans are like animals, animals are like the sea, the sea is like an animal, the land is like the sea. The work of the metaphors in this story is to reinforce the reality of interdependence and blur the lines of identity between creatures. Humans and horses are different, of course, but not so different: not so unalike as we would have to believe if we want to be free to own and abuse them.

This blurring, it occurs to me, is something biblical metaphors often do, too. There are distinctions, and roles, identities given in the garden, but then all those things are blurred. The Bible isn’t interested in maintaining unchanging and unchangeable categories. There are Israelites and non-Israelites: but here is Rahab, here is Ruth: enemies can become friends. Humans are tasked with ruling; so are the sun and the moon. Humans speak. So do donkeys. Humans mourn. So does the land. God makes a covenant with Abraham. God has also made a covenant with the earth. It’s connection, not separation, that defines creation.

*

Along with my horse phase, there was a puppy phase — mostly inspired by Jean Smart’s Mine for Keeps, also involving a wall calendar, and cut short when my pleas for a puppy of my own were answered. It was a matter of weeks before I came to realize that what I liked was not dogs, but dogs in books. Dogs required so much care and attention.

It’s not something for which I’m constitutionally suited — the real-life love of animals, the daily recognition of our interdependence. It’s not something for which I’m constitutionally suited — but at least I can keep working on my metaphors.

Three Things:

The latest essay at Collegeville Letters begins with a peek into the dark and twisted world of the text messages Lauren and I send each other

For Mother’s day: I love the tension in this Catherine Wiley painting I encountered last week:

Are you in Western North Carolina? Come hear Jeff Chu at Trinity next week — Amanda Held Opelt will be there playing music, too. Free event! (Scroll down and RSVP here.)

Buy my books here.

It has been two months since I have read one of your posts. So thankful that you are here on Substack and I can find you words when I need them.

I made my father take me to Chincoteague after first reading that one, and my prized possession then was a little figurine of Misty that I bought at the gift shop. If he read this post, he’d tell you about my resulting encounters with Delaware’s “wild cows” that resulted in a Wilmington News Journal article. The idea of a wild thing freed from human systems of consumption was captivating and formative. Don’t even get me started on my other beloved book of that era: Island of the Blue Dolphins. Well, I guess am off to go convince someone here to go see Colorado’s wild horses with me!