Enemies, Four Ways

I would really rather not cook dinner for them, tbh

Through a bit of miscommunication, I prepared a sermon this week and then had no pulpit in which to preach it. So, I played around with it a little and am sending the revised version on to you.

In the presence of mine enemies, because God has finally smote (smited?) them like I asked

I’m walking the loop around the French Broad River with Jessica, asking her about enemies, and reciting Psalm 23 in the King James Version (the only authorized version for Psalm 23, no others need apply) so we can hear aloud the full context of this phrase, “in the presence of mine enemies.” When I was a child, I tell her, I always imagined the scene one way, with enemies bound up in the corner and hungry, forced to watch as God set out a banquet for the Psalmist.

Wow, she says, grinning. That tells me everything I need to know about you as a child.

We laugh. I blame shift: or everything you need to know about the religious environment in which I was raised, I say.

But, really, is it so wrong to imagine it this way?

Enemies are a constant refrain in the Psalms.

There are questions: Why do my enemies prosper?

There are requests for harsh and violence punishments to befall enemies: Deliver me, O my God! For you strike all my enemies on the cheek; you break the teeth of the wicked…Silence my enemies; destroy all my foes.

There are proclamations of God’s victory over enemies: The enemies have vanished in everlasting ruins; their cities you have rooted out; the very memory of them has perished.

All I’m saying is there are good reasons for me to think the Psalmist might want his enemies bound in the corner and tortured by the smells of slow-roasted meat and fresh bread and a nice cabernet.1

In the presence of mine enemies, because God has declawed them at least for the moment

Or maybe I haven’t always imagined it quite that vindictively. Maybe I’ve also imagined:

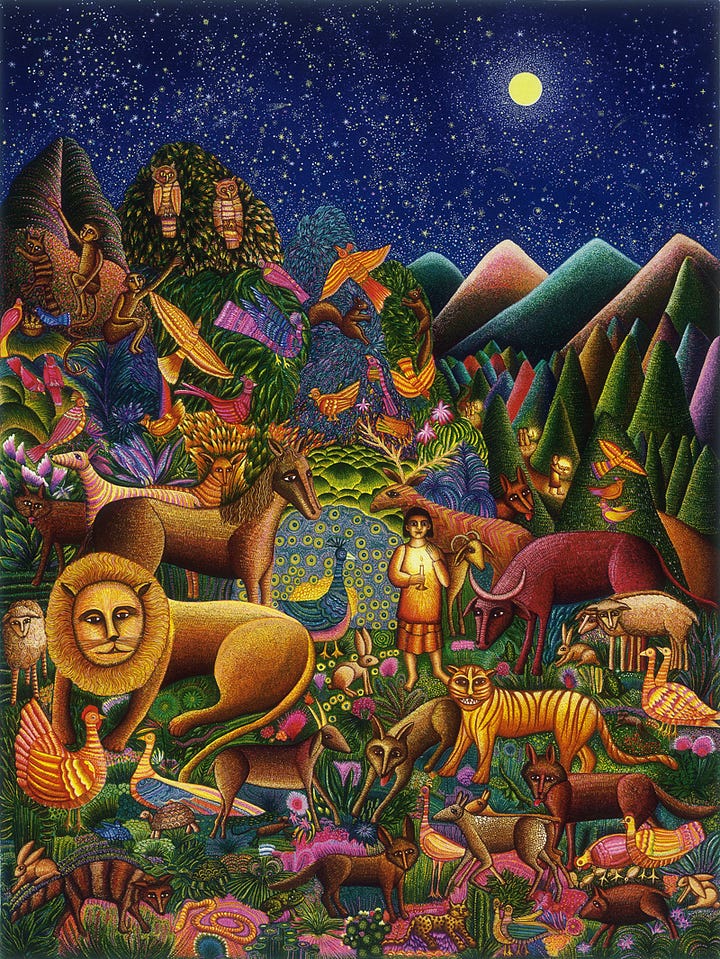

David, trying to escape King Saul’s wrath, running through dark woods, exhausted, hungry, sure he’s about to die; and God stopping him, weaving some invisible wall of protection around him, magicking up a heavily-laid banquet table in the forest, and feeding him while King Saul’s soldiers lurk in the shadows and watch from behind trees, unable to touch David as long as he’s protected — but also unable to join in the feast.

This gets closer to Jewish tradition about the Psalm’s origin: Rashi teaches that the Psalm was composed by David on the run from King Saul. While “hiding in the dry Judean forest of Hereth, and on the brink of death without food or drink, he was miraculously saved by G-d, who nourished him with a taste of the World to Come.”

Structurally, the Psalm is bracketed by Yahweh: it begins and ends with the Lord. And count up the words, and at the very center is the phrase for you are with me.

This is a poem about being safe when bracketed by God, even if your enemies end up in the bracket and bracken with you.

In the presence of mine enemies, whom God has invited to the table

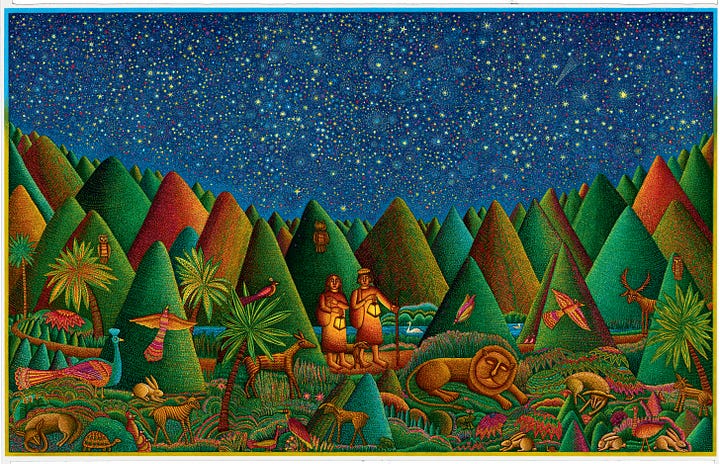

A couple of weeks ago, I preached at a funeral. The family had selected texts for the service from those suggested in the BCP, and we read Psalm 23 immediately after Isaiah 25. In Isaiah’s vision of eschatalogical hope, there are a lot of people at the table:

On this mountain the Lord Almighty will prepare

a feast of rich food for all peoples,

a banquet of aged wine—

the best of meats and the finest of wines.

On this mountain he will destroy

the shroud that enfolds all peoples,

the sheet that covers all nations;

he will swallow up death forever.

The Sovereign Lord will wipe away the tears

from all faces…

And with these two texts in such close proximity, the feasts merged in my mind for a moment. What if “Thou prepares a table for me in the presence of mine enemies” means my enemies are invited to the banquet, too?

Isaiah and Psalm 23 share this vision of a feast; they also share language about sheep. In Isaiah 11, the future that God has prepared for us is a future in which the lion and the lamb live peaceably together.2

Perhaps the Good Shepherd invites the wolf to the table.

Perhaps the enemies aren’t bound in the corner, but picking up their forks and passing the potatoes.

What does it mean if part of God’s tender care for us — part of the way God provides for us in personal, lavish, loving ways —

is that in those intimate moments of provision, God invites our enemies in?

Psalm 23 is a poem. Isaiah 25 is a poetic vision of a peaceful future. They’re descriptive, not prescriptive (and later, when Jesus says we ought to love our enemies, He doesn’t say we need to invite them to dinner). This is not a call for a victim of abuse to invite her abuser over, or for an undocumented immigrant to prepare a meal for an ICE agent.

But it is a vision we can learn to hope for. We can learn to hope that God adores our enemies, knowing that to be adored by God, and to know it, is to be cleansed by a fire that burns away all those things in us that should not endure.

And it is a vision we can learn to trust: to believe that if God sets the table, and brings you and an enemy there together, you need not fear, for God is with you.

I know that breaking bread with opponents does something. I know this because of Matthew Stevenson, the Orthodox Jew at New College who invited a prominent white nationalist to shabbat dinner. I know this because of blues musician Daryl Davis, who started intentionally befriending members of the KKK.

At the very least, if God brings us to a table with our enemies, God protects us from each other. At best, while we’re breaking bread together, God shows us to each other. We see the humanity and the belovedness of even our enemies, and we are both changed.3

In the presence of mine enemies, because I am never without them

But perhaps there is only one person at the table. And it is me.4

The table is also an invitation to be honest about the reality that some of my worst enemies dwell within.

God prepares the table in the presence of my pride; my judgmentalness; my desire for God to strike my enemies and give them a painful death; my closed mind, my fear, and greed, and illicit desires, and complacency, and white lies. God invites me to stop trying to hide the things I’m ashamed of, and to lay them out on the table for us to see.

And then, God sets the table. God anoints my head with oil. My cup overflows.

Three Things:

Today, three poems for the table:

Red Brocade

by Naomi Shihab Nye

The Arabs used to say,

When a stranger appears at your door,

feed him for three days

before asking who he is,

where he’s come from,

where he’s headed…[full poem]Perhaps the World Ends Here

by Joy Harjo

The world begins at a kitchen table. No matter what, we must eat to live.

The gifts of earth are brought and prepared, set on the table. So it has been since creation, and it will go on… [full poem]Love After Love

by Derek Walcott

The time will come

When, with elation,

You will greet yourself arriving

At your own door, in your own mirror,

And each will smile at the other's welcome,

And say, sit here, Eat… [full poem]

And maybe I need to see myself not as the speaker in this poem, but as the enemy. After all, I have more in common with the powerful oppressors than the vulnerable oppressed.

apparently this is more properly translated wolf

Were we in church, I might also say here that every week we come to a table that Jesus set in the presence of His enemies. I might say that the kind of shepherd who invites the wolf to the table with his lambs is the shepherd who gives his own body to be the feast. I might say that we only draw near to this table after proclaiming “The peace of the Lord be always with you” — a peace that became possible through that table.

(hi, I’m the problem, it’s me)

Some passages of scripture only sound right in the King James Version, lol.

I love this (and, I believe, the nod to Capon in the title?) ... I also pray this sermon lives on here in the interwebs (and our hearts) forever.