I was eighteen when I heard that the author had died. It was old news, at that point: Barthes had made the argument in 1967. By this time, the nineties, postmodern literary criticism was big in college English departments, and for a while I found conversation about it pretty endlessly juicy, not just for what it did to “authority,” but for what it did to my sense of myself as a reader. Maybe what the author intended could never really be known, and maybe her intentions didn’t matter, and maybe readers were co-creators of the meaning of texts. For a final paper in a Shakespeare class, I performed postmodern literary criticism on postmodern literary critics of King Lear, and my curmudgeon of a professor was so delighted he wanted to send me to phd school in Illinois. I went to Southeast Asia instead, and had I made my choices in life a little differently, I imagine I could tell you what college English departments are saying about all these things now, but alas I cannot.

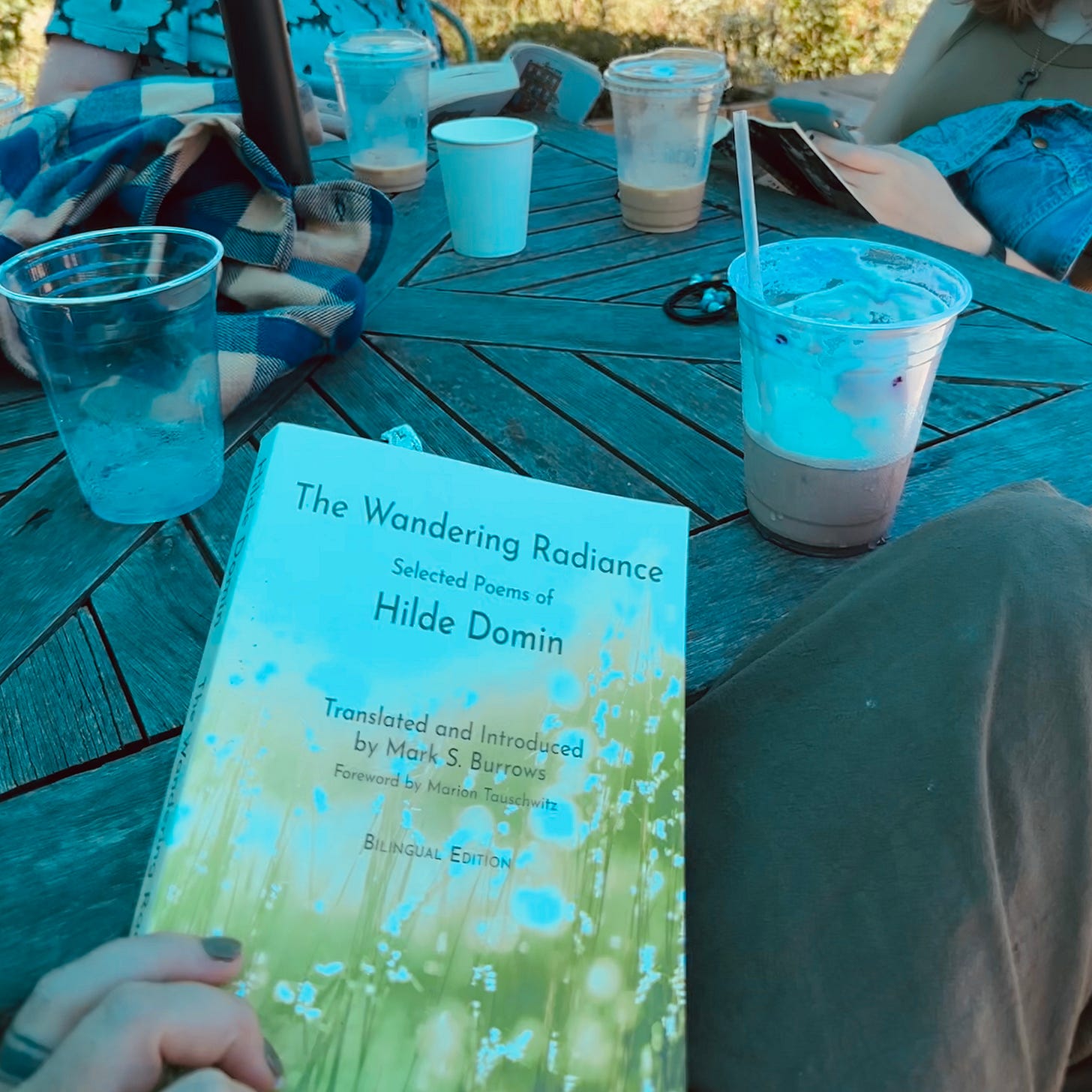

But I can tell you what German Jewish poet Hilda Domin said, several years before Roland Barthes, about the interplay between the author and readers of her own poems.1 Domin fled Germany in the years before World War II, but returned in the 1950s. In an essay describing her vocation as a “poet of the second chance,” and the meaning of writing poetry in times of social upheaval, Domin wrote:

“I don’t believe, though, that poems are an ‘object of use’ [Gebrauchsgegenstand] like those that can be ‘used up.’ Rather, they belong to those magical ‘objects of use’ which, like the body of a lover, come to flourish in being drawn upon.”

Texts – poems – respond to us like the body of a lover. Some are familiar lovers, soft, reliable, comforting, Rilke’s “Autumn.” Others startle us awake, show things to us we’ve never seen. Lovers and poems both change — for the better, flourish — when we draw upon them, they shapeshift, they mean differently.

And Scripture, too, even more magically, comes alive as we inhabit it. Imagine Scripture as the body of a lover, a long-term lover, boring sometimes, too familiar; but then, flourishing when we draw upon it. That mutual revivification may be more endlessly juicy than any question of authorial intent Barthes wanted me to ask.2

Three Things:

Here’s one of her poems:

Don’t Grow Weary

Don’t grow weary

but hold your hand out

quietly

to the miracle

as if to a bird.

(I love, among other things, that “don’t grow weary” isn’t here a call to work, just a call to hold out our hands to receive the miracle.)Ricotta Pasta Alla Vodka, the best meal I made last week

Reservation Dogs, streaming on Hulu, just wrapped up its third season. About Native teenagers in Oklahoma, it’s unlike any other show I’ve watched in pacing, storytelling, characters, spirituality, and humor, and I really loved it.

Where Goodness Still Grows is available wherever books are sold. My first book, Dangerous Territory, has a second edition coming this November; you can pre-order it now at Bracket Publishing.

Lauren gave me this book last week because she is an endlessly good gift-giver. In the other line from the Introduction that keeps ringing in my mind Domin sees “the poet’s vocation as living in answer to the ‘call against programmability.’” Yes, she said this before or around the same time as Wendell Berry said “every day/ do something that won’t compute.”

See what I did there